I was seven when my grandmother taught me the first rule of gift-giving. We were sitting at her kitchen table, surrounded by scraps of wrapping paper, ribbons curling around our fingers like little snakes. I was struggling to wrap a birthday present for my cousin Mia—a dolphin charm bracelet I’d spent weeks saving up for.

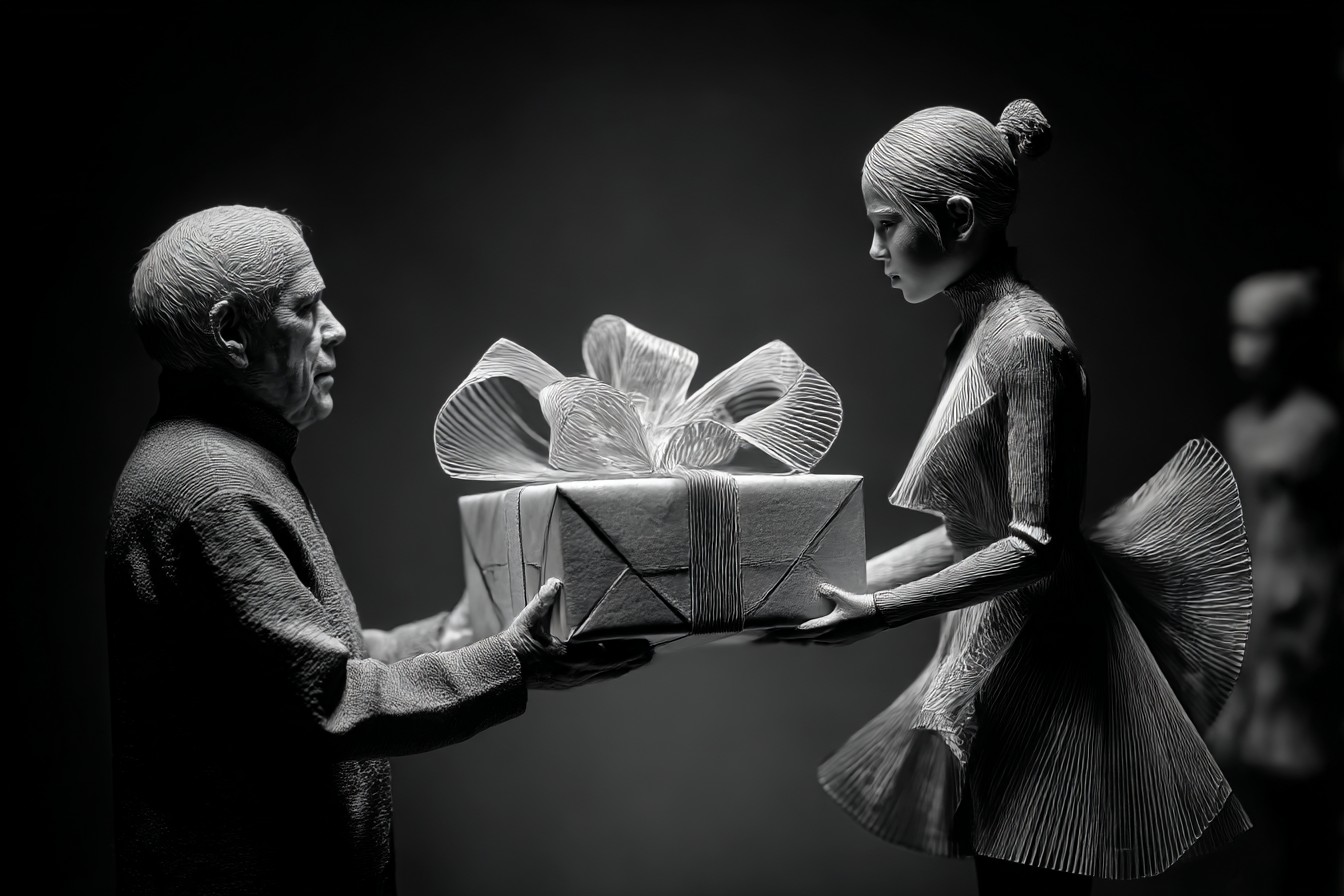

“Not like that, Livvy,” Nana corrected gently, taking the scissors from my hand. “You’re rushing. A gift isn’t just about what’s inside the box. It’s about the whole experience.”

I remember rolling my eyes dramatically. “But Mia’s just gonna rip it open anyway!”

Nana smiled that knowing smile of hers, the one that made her eyes crinkle at the corners. “Maybe. But the way you present something matters. It shows you cared enough to take your time.”

That afternoon in Nana’s kitchen was the beginning of what would become a lifelong education in the art of giving. My grandparents—both sets of them, actually—were masters of thoughtful generosity. Not because they had loads of money (they definitely didn’t) but because they understood something fundamental that seems to be getting lost these days: gifts aren’t just stuff. They’re messages. They’re connections. They’re little pieces of yourself that you’re handing over to someone else and saying, “I see you.”

My grandfather Frank (Dad’s dad) was the absolute king of unexpected gifts. He never, and I mean NEVER, bought anything predictable. One Christmas when I was nine, everyone was getting very sensible presents—new slippers, sweaters, books. And then Grandpa Frank handed me this oddly shaped package wrapped in the comics section of the newspaper (his signature wrapping paper). Inside was a telescope—not a toy one, but a proper beginner’s telescope.

“You mentioned in July that the stars looked different at our cabin than they did at your house,” he said when I looked up at him, confused. “Thought you might want to take a closer look.”

I’d completely forgotten making that comment during our summer vacation. It was just something I’d said while we were sitting on the porch after dinner, nothing important. Except to Grandpa Frank, it was important. He’d filed it away for five whole months. That telescope became my prized possession through middle school. I even joined the astronomy club because of it. And every time I used it, I remembered that Grandpa Frank had really, truly listened to me.

That was his gift philosophy—listen carefully, remember everything, and give people what they didn’t even know they wanted. It wasn’t about grand gestures or expensive items; it was about paying attention. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched friends and family unwrap his presents with that same confused look I must have had, followed by this dawning realization that he’d somehow reached into their brain and pulled out a desire they’d mentioned once in passing months earlier.

My maternal grandmother had a completely different approach. Nana Rose believed gifts should be practical first, delightful second. “No dust collectors,” she’d declare firmly. “If it sits on a shelf looking pretty but doing nothing, it’s not a proper gift.”

This philosophy came from growing up during wartime rationing in England. Nana Rose didn’t believe in waste of any kind, including wasting money on trinkets that served no purpose. But—and this is the important bit—she didn’t think practical meant boring. The winter I turned 13, she gave me a handmade quilt for my bed. Practical, right? Except she’d secretly collected fabrics that represented my interests and passions throughout the year.

There was material from an old concert t-shirt I’d outgrown but couldn’t bear to throw away. A patch from the first theater production I’d been in. A piece of the hideous floral curtains from our lake house that had somehow become a family joke. Each square told a story. I still have that quilt, now faded and worn from two decades of use. When Jake and I were first dating, I caught him examining it one morning.

“This is incredible,” he said, tracing the patterns with his finger. “It’s like your entire childhood in blanket form.”

“That was Nana Rose,” I told him. “Practical but meaningful. She didn’t do useless gifts.”

Sometimes I think about how my grandparents would navigate today’s gift-giving landscape. We’re all bombarded with targeted ads and “ultimate gift guides” and the constant pressure to buy, buy, buy. Social media has created this weird expectation that every gift needs to be camera-ready, Instagram-worthy, part of some elaborate unboxing ritual. Gift-giving has become this competitive sport where the goal seems to be either maximum shock value or maximum monetary value.

I got caught up in it myself a few years ago. For Jake’s 30th birthday, I went completely overboard planning this elaborate series of gifts that would arrive throughout his birthday week, each one more extravagant than the last, culminating in a surprise party with all his friends. I spent weeks organizing it all, secretly congratulating myself on what an AMAZING wife I was being.

About halfway through the week, after I’d presented him with yet another carefully wrapped package with an elaborate backstory, Jake gently took my hands and said, “Liv, this is all incredible, but you know what I’d really love? Just a quiet dinner with you where you’re not stressing about the next surprise.”

I was initially crushed. I’d put so much effort into creating this perfect gift experience, and he wasn’t appreciating it properly! But later that night, I remembered something my grandfather used to say: “The best gift is one that meets the recipient where they are, not where you want them to be.”

Jake didn’t need a week-long extravaganza. He needed quality time without pressure or performance. I’d been so focused on creating the perfect giving experience that I’d completely missed what would actually make him happy.

That’s the problem with how gifting culture has evolved. We’ve gotten so caught up in the performance of giving—the beautiful packages, the surprise factor, the social media potential—that we’ve forgotten the fundamental purpose: to connect, to show we care, to make someone else feel seen and known.

My grandparents never worried about whether a gift would photograph well for social media. They never stressed about whether their presents measured up to some arbitrary standard of impressiveness. They simply paid attention to the people they loved and tried to give them something that would bring genuine joy or usefulness.

Grandpa Frank would probably be baffled by gift cards, which now make up something like 60% of holiday giving in the US. “Why would you give someone money they can only spend at one store?” he’d ask, genuinely confused. “If you don’t know them well enough to pick something out, just give them cash.”

And yet, there’s something my grandparents understood that transcends all the cultural changes around gift-giving: the importance of putting thought into presents. Real thought, not just the performative kind where you buy something expensive to show you care.

Last year, I was completely stuck on what to get my brother for his birthday. Tom is notoriously difficult to shop for—he buys whatever he wants for himself, rarely expresses specific desires, and responds to direct questions about gifts with the infuriating “Oh, I don’t need anything.”

I was browsing around yet another website, feeling increasingly desperate, when I remembered a conversation we’d had months earlier. We’d been talking about our childhood, and Tom mentioned that he missed the elaborate blanket forts we used to build in the living room when our parents were out. “Remember how we’d use all the dining chairs and Mom’s good sheets? And we had that flashlight with the red filter that made everything look spooky?”

Instead of buying him something, I created a “Blanket Fort Emergency Kit” for his apartment—clamps to secure blankets to furniture, battery-powered string lights, a flashlight with colored filters, some ridiculous snacks we used to smuggle into our forts as kids, and an illustrated “Fort Construction Manual” I made myself with inside jokes and references to our childhood creations.

When he opened it, Tom laughed so hard he actually snorted, which he hasn’t done since we were teenagers. Then he immediately started rearranging his living room furniture to construct a fort, despite being a 35-year-old investment banker who was hosting a dinner party the next evening.

That gift cost less than $40 to put together. But it connected us back to shared memories and gave him permission to do something purely fun and nostalgic. Nana Rose would have approved of its practicality (hey, everyone needs emergency fort supplies), and Grandpa Frank would have appreciated that it came from really listening.

I think about my grandparents’ gift wisdom often in my work now. When I’m helping clients select corporate gifts or advising friends on wedding presents, I find myself channeling those lessons from childhood:

From Nana Rose: Is it useful? Will it last? Does it serve a purpose beyond looking pretty?

From Grandpa Frank: Does it show you’ve been paying attention? Will it surprise and delight them in a way that feels personal?

From both of them: Does this gift create or strengthen a connection between giver and receiver?

The world has changed enormously since my grandparents were my age. We’ve got AI gift selectors now, subscription boxes for every possible interest, and the ability to send presents across the world with a few clicks. But the fundamental truths about meaningful giving haven’t changed at all.

Good gifts—truly good gifts—aren’t about the price tag or the presentation. They’re about the connection. They’re about saying, “I see you. I know you. I value you enough to pay attention to who you really are.”

In our rush to find the perfect present, we sometimes forget that the most valuable gift we can give is our attention. When my grandfather remembered my casual comment about stars five months later, what touched me wasn’t just the telescope itself. It was knowing that he’d been listening closely enough to remember something I’d forgotten myself.

That’s the intergenerational wisdom I try to carry forward. In a world of instant gratification and one-click shopping, the gifts that matter most still come from the same place they always have: genuine care, thoughtful attention, and the desire to bring someone else joy.

And yes, I still wrap presents the way Nana taught me, taking my time with the corners and making sure the ribbon curls just right. Because sometimes the old ways are still the best ways—and because every time I sit down with paper and scissors, I feel her right there beside me, gently guiding my hands.